Artists: Alexandre Alexeieff & Claire Parker, Max Almy, Berthold Bartosh, Claudio Cintoli, Segundo de Chomón, Émile Cohl, Maya Deren, Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, Ed Emshwiller, George Griffin, Noa Gur, Claus Holtz & Harmut Lerch, William Kentridge , Fernand Léger, Len Lye, Norman McLaren, Diego Perrone, Fratelli Quay, Robin Rhode, Jan Švankmajer, Stan Vanderbeek, Kara Walker.

Edited by Lorenzo Giusti and Elena Volpato

From 30 May to 29 June 2014 the MAN museum in Nuoro presents the exhibition “Passo a due. The avant-gardes of the movement”. The project, curated by Lorenzo Giusti, director of the MAN Museum, and Elena Volpato, curator of the GAM in Turin, responsible for the Artist’s Film and Video Collection, delves deeper, through a cross-section that from the origins of animated cinema to the present day , one of the most fascinating aspects of animation works, that possibility cherished by many artists and filmmakers of using filmic movement as a magical ritual that gives life to the drawing line, the silhouette, the puppet or the photographic image.

The creative, properly demiurgic imagination, which is often underlying drawing and representation through figures, takes on the bewitching traits of enchantment, of a life that is a dance of fantasy, through movement and musical rhythm. It is no coincidence that artists and film-makers, when approaching the different animation techniques, often focus on the body image and link to it evocations of the figure of Frankenstein, the Golem or the robot, and in general of artificial birth of a body, as if they wanted to repeat in the mythical tale their own power as animators: to give soul to the inanimate.

The works on display therefore offer the possibility of a historical journey in experimental and artistic animation, through the image of the body, its construction and its “assembly”. When the animation is based on drawing everything seems to arise from a line, as in pioneering Phantasmagoria by Émile Cohl (1908) or in Lifeline (1960) by Ed Emshwiller, where the continuous white line is enveloped in knots of matter which little by little become organic arabesque, mixing with the photographic image of a dancer’s body. Or as in Head by George Griffin (1975), where the basic shape of the face and the artistic tradition of the self-portrait are stripped of any realistic detail and then unexpectedly revived with emotional expressiveness and psychological nuances rendered pictorially.

In other works the drawing leaves room for sculpture and the myth of Pygmalion connected to it, as in the case of Jan Švankmejer who in Darkness Light Darkness (1990) shows a body capable of self-shaping, starting from the two hands, closed in a room, into which all the limbs flow in sequence to form a unit. Švankmejer’s two hands have an antecedent in the surrealism of Alexeieff and Parker with The nose (1963), where single, rebellious and independent arts claim for themselves the power of the vital spell, and seem to find a recent development in some works by Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg.

The tale of Frankenstein lives explicitly in Len Lye’s film, Birth of a robot (1936) and again in Street of Crocodiles (1986), by the Quay Brothers, or in the video by Max Almy, The Perfect Leader (1983), where what is artificially constructed is not a creature destined to serve its creator, as in Frankenstein and the Golem, but it is the future political leader who is programmed on the computer so that in his dictatorial ferocity he reflects the society that wanted him and created.

Other works represent the body as a place of construction, not of individual identity, but of social identity. This is the case of the famous one The idea (1932) by Berthold Bartosh, but also, in a different way, by the works of William Kentridge, in which the pain of the masses leaves traces of black dust on the white pages of history compared to the immodest bodies bathed in the blue water of the rich tycoons. This is the case of Kara Walker’s silhouettes, also black against the white background, tortured and violated by colonial ferocity.

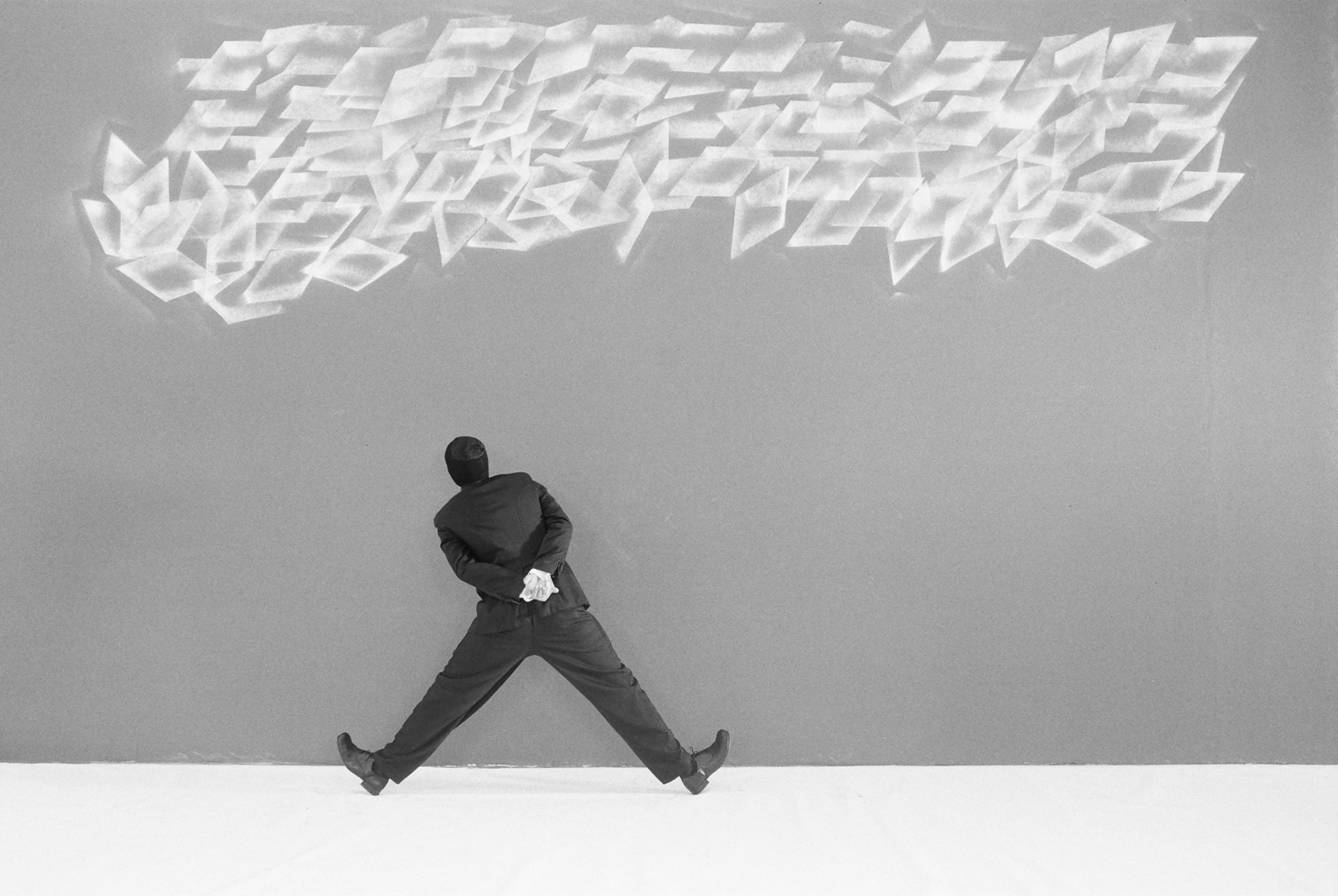

Finally, it is dance, the ultimate expression of beauty in movement, which allows us to show the magic of the animated body in the most diverse places of thought and imagination: in Easter Eggs by Segundo de Chomón (1907), in Ballet Mecanique by Fernand Léger, where machine and body tend to merge into a single moving subject, in the absolute space of Pas de deux by McLaren, on the astrological night of The Very Eye of Night (1958) by Maya Deren or in the two-dimensional universe of Robin Rhode’s drawing, where body and drawing meet on a single plane of reality and dream.

The itinerary is completed by the works of Claudio Cintoli (More, 1964), in which the aesthetic matrix of Pop Art disarticulates the identity of the body in clothes and advertising products; by Stan Vanderbeek (AfterLaughter, 1982), where the movement of the body in space becomes modified through time, as in a phylogeny of the human, and by Claus Holtz & Harmut Lerch (Portrait Kopf 2, 1980) in which the overlapping animation of faces and heads leads, in a backwards, anti-Lombrosian path, to an original unity of the human trait. Finally, the most recent works by Diego Perrone (Totò naked, 2005) where the icon of Totò is broken down and recomposed with a mechanism that does not forget the actor’s ability to become a puppet, an inanimate body, and Noa Gur (White Noise, 2012) whose linguistic essentiality ideally closes the journey, restoring the ancient root of drawing to the animation of the body: the capture, through the simple technique of the imprint, of an individual and his vital breath.

A bilingual catalog published by NERO will accompany the exhibition.